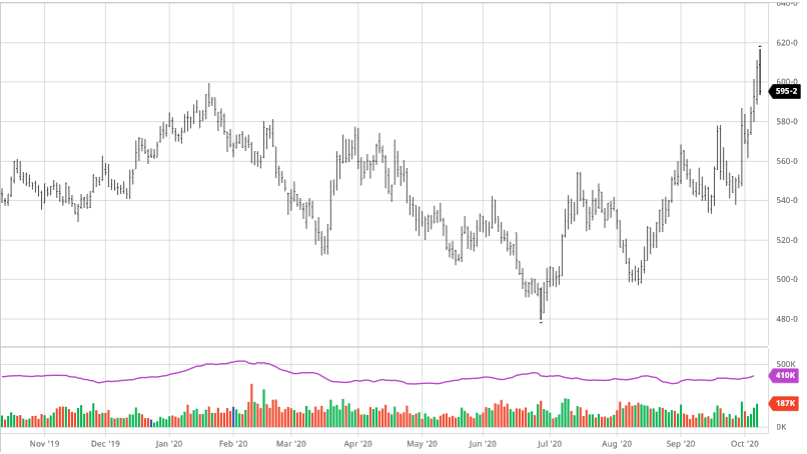

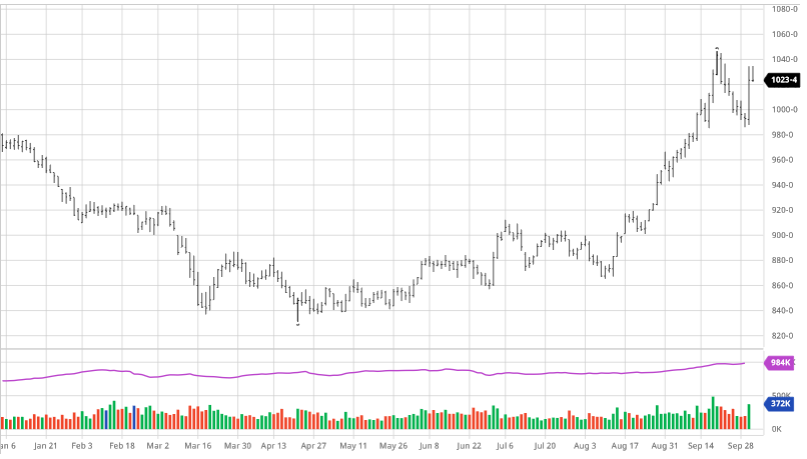

Corn was unchanged over the last 2 weeks as it has been range bound between $4.20 and $4.40 as you can see in the chart below. This is the first stretch like this since corn began its climb up, as there hasn’t been any new news to really propel it. China continues to be the main buyer as we have come to expect, but with no surprise sales or weeks above expectations that hasn’t been enough to break through. The break followed by a bounce is good to see as markets remain bullish, but needed a correction along with the end of the December contracts in the last couple of weeks. Chinese demand of corn will continue to be the bullish news as we look for that to continue.

Via Barchart.com

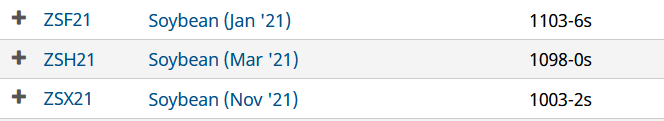

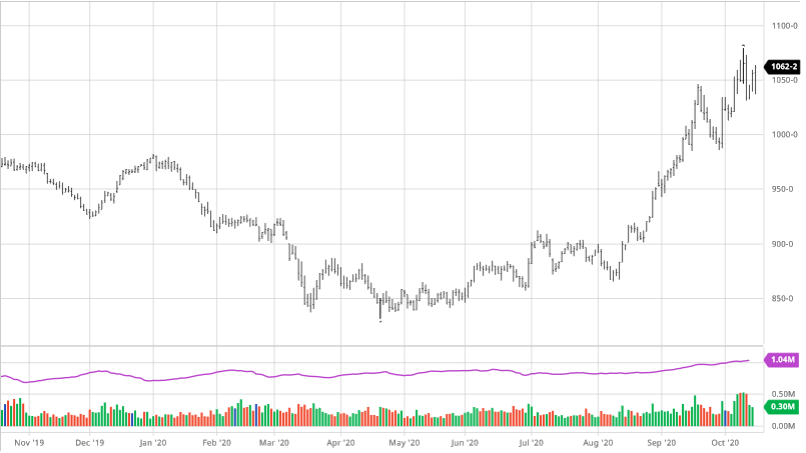

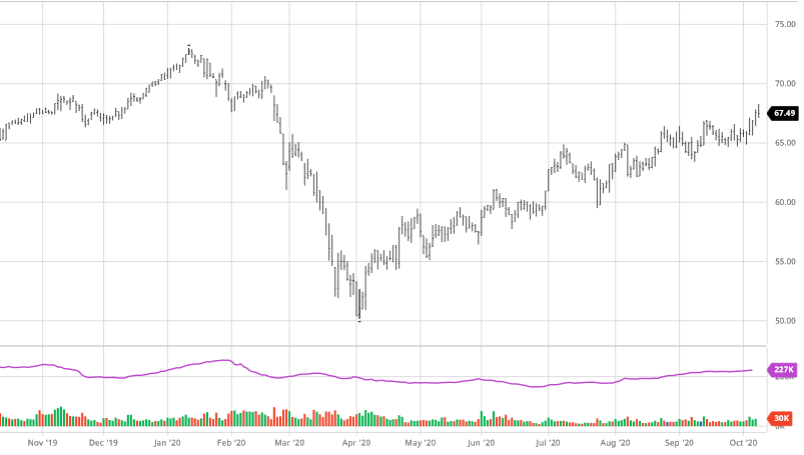

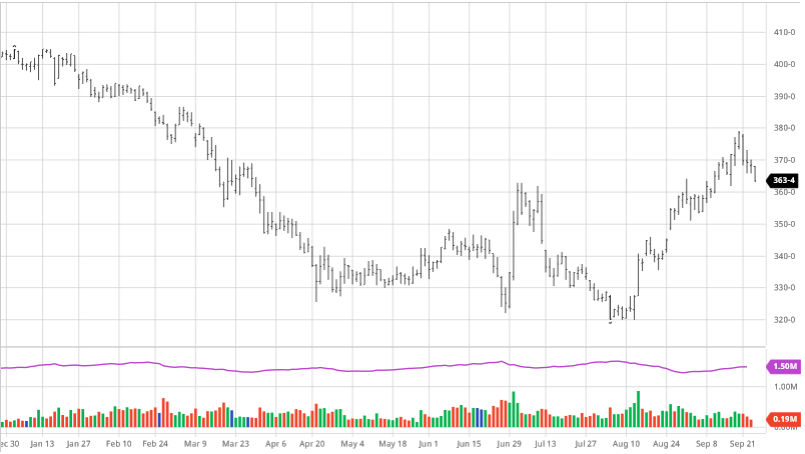

As you can see from the chart below beans have had a couple decent size swings in the last two weeks despite only being down 10 cents over that time. In that span we have seen January soybeans touch $12.00 and dip to $11.43 before the recent bounce back. The good news is it appears that Chinese buying should help keep some support under soybeans as they will look to be aggressive buyers when price falls (like the recent 50 cent dip then bounce back). South America will get some rain across Brazil this week, but the La Nina pattern looks to bring hot and dry weather in the coming months during an important stretch. After the fall at the start of the week it is nice to see a bounce back to current levels showing there is still bullish support. With funds continuing to be near record long, when they decide to take profit we may see dips similar to this week. We continue to hold the same strategy of not storing beans into the new year and take advantage of strong prices while if you believe markets are going higher to look at ownership on the board.

Via Barchart.com

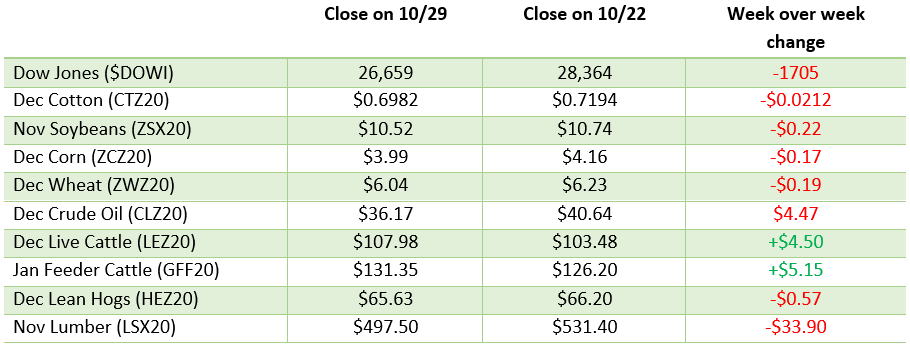

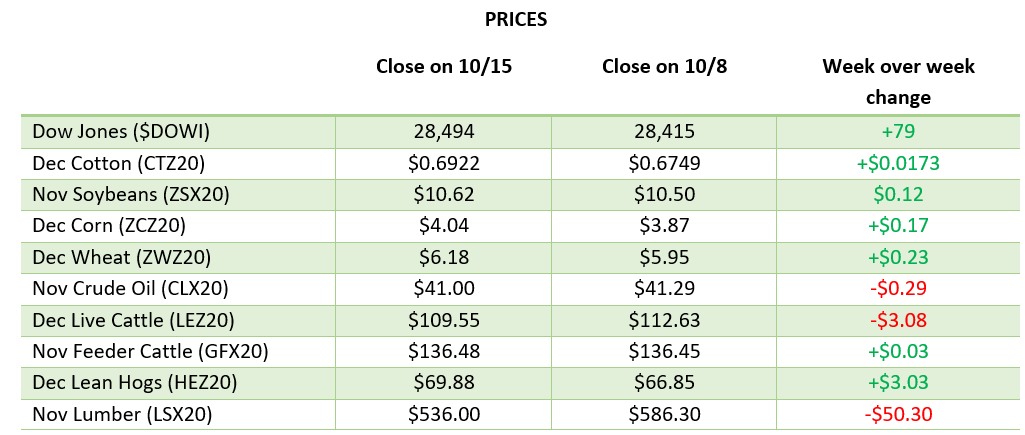

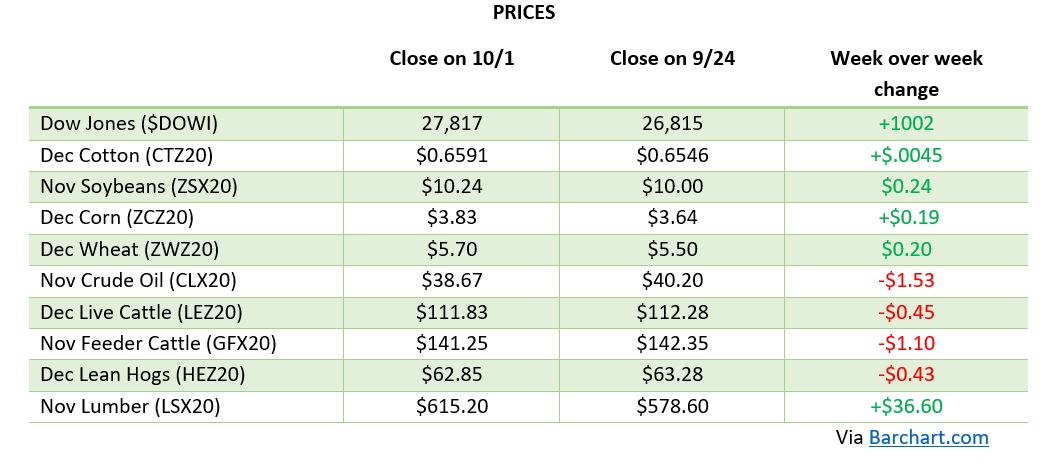

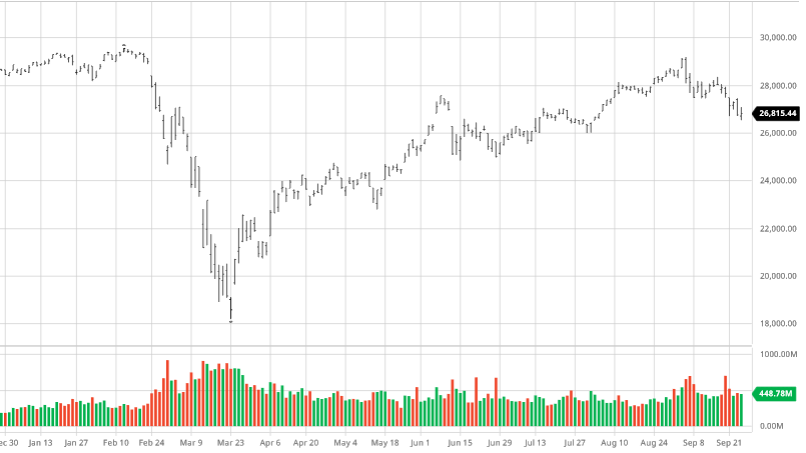

Dow Jones

The Dow has traded over 30,000 several times over the last 2 weeks, but has failed to hold onto that number for a longer run up. Positive vaccine news and the possibility of vaccinations starting this month were the main driver to get it to this point. Stimulus talks have resumed as well, with some sectors getting boosts from investors expecting targeted stimulus to certain sectors (airlines as an example).

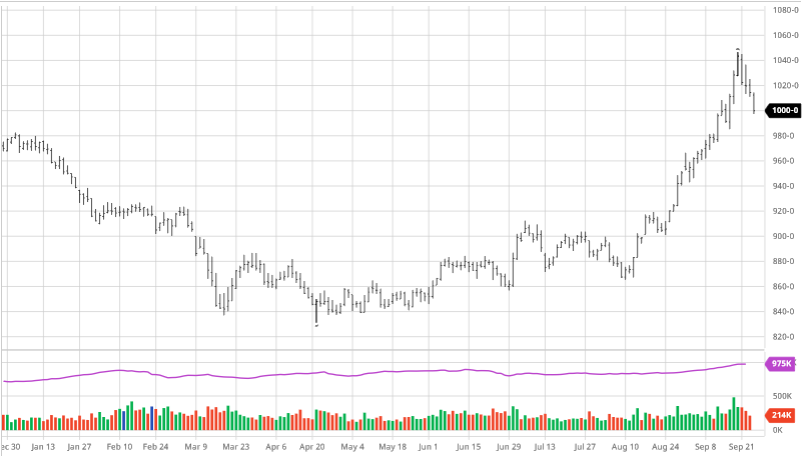

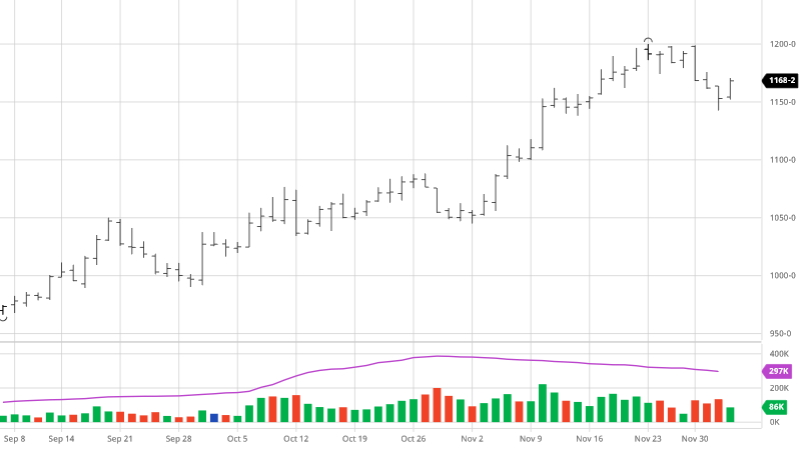

US Dollar

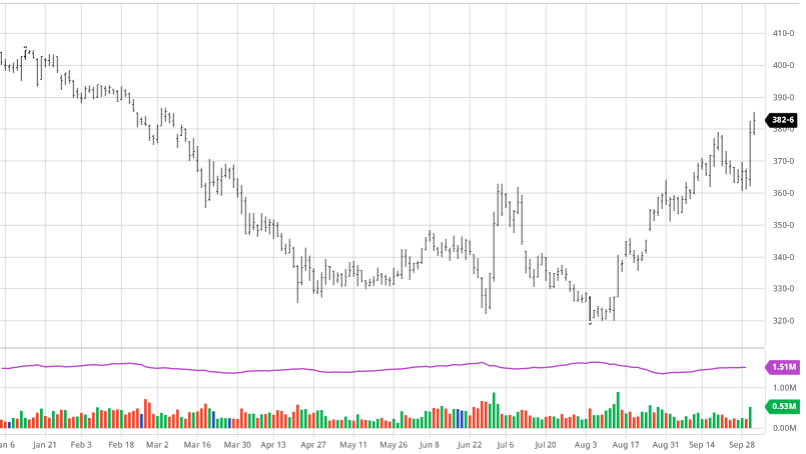

The USD has continued its fall over the last couple of weeks. The 3-year chart below shows where the USD is relative to the past few years and shows that we are at levels not seen since early 2018. A weaker USD helps US commodities and makes them more competitive on the world market.

Via Barchart.com

Phase 1 Trade Deal

Just a quick note: Joe Biden said he will not immediately cancel the Phase 1 trade deal with China or take steps to remove tariffs currently in place.

Via Barchart.com

Via

Via