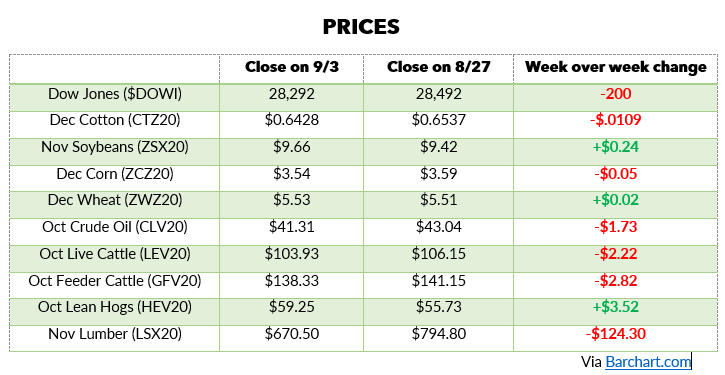

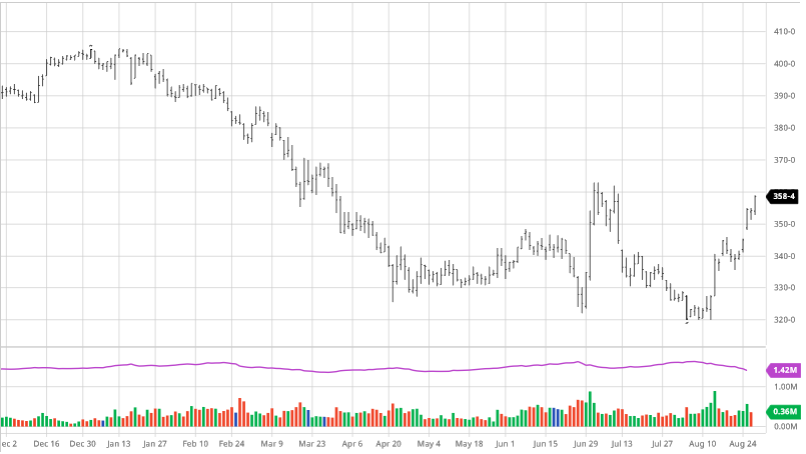

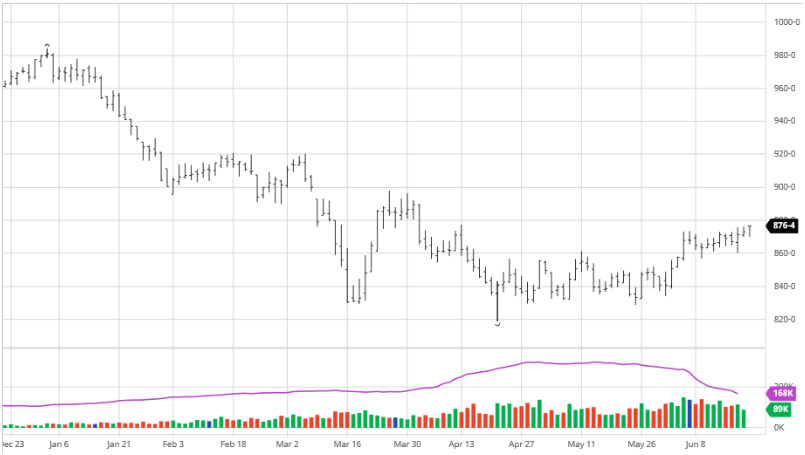

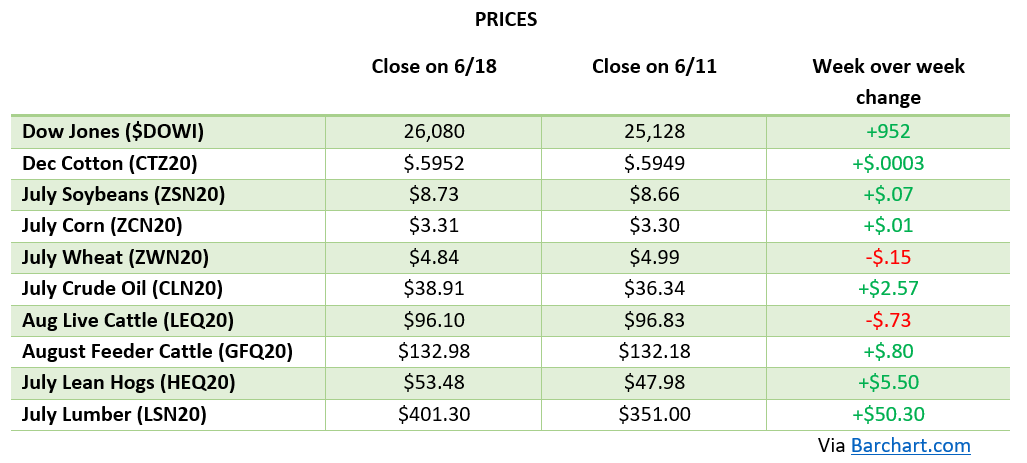

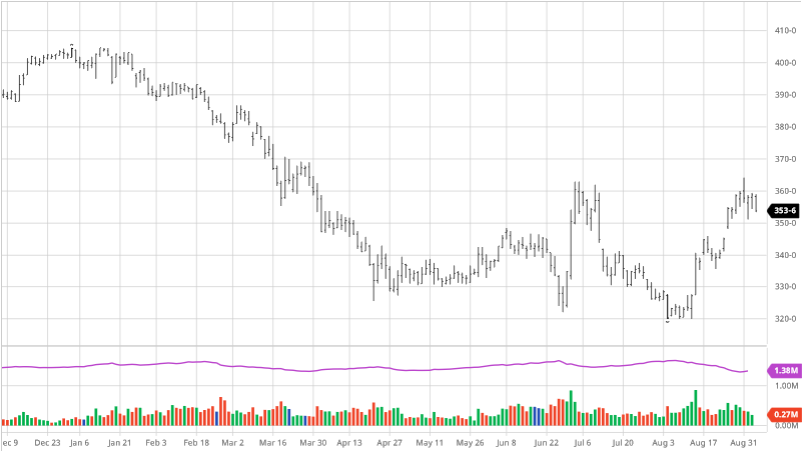

Corn saw slight loses on the week after trading in the low $3.60s despite strong export numbers and falling crop conditions. The crop conditions at this point usually fall as corn starts to get ready for harvest and lose its color as ratings come from looking at the fields rather than any testing. As China has continued to be a large buyer it looks like the market has factored in their purchases and will expect similar levels or purchases moving forward. The forecasts have some rain in much needed areas as we get closer to harvest to help hold on to what many expected to be a great crop a month ago but has seen stress as of late. Rain over the weekend is expected for much of the corn belt especially in areas of the WCB that have been the driest. Although the rain may be late to help out corn much it should give the beans in those areas help. Look for the trade to hold its breath and trade in the $3.50-$3.60 range as everyone holds their breath in anticipation of the USDA Report next Friday.

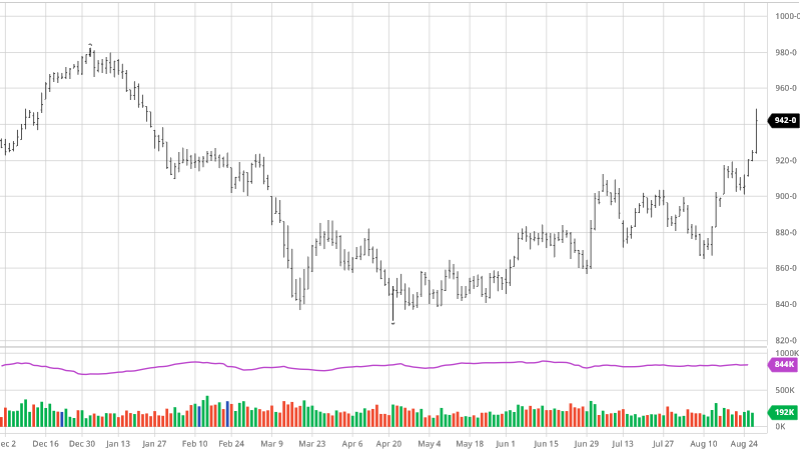

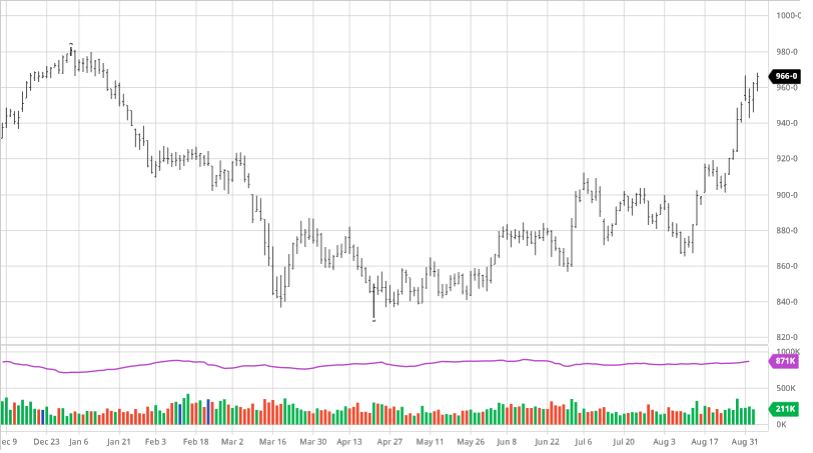

Soybeans continue its climb higher as exports continue to be huge. Despite a bearish change in the weather with widespread rain coming this weekend the demand continues to pull beans higher. The rain could be coming at just the right time in certain areas as yields can still be effected. One private yield estimate from StoneX pegged the US bean yield at 52.9 bushels. This would be a larger trend line yield but with the increased demand from China it would not crush prices moving forward. Keep an eye on other private estimates as we head into the USDA Report next Friday to hopefully get an idea what the USDA might come out with. Look for exports to continue their strong run as any pullback would hurt prices that have been drawing their strength from recently.

DOW Jones

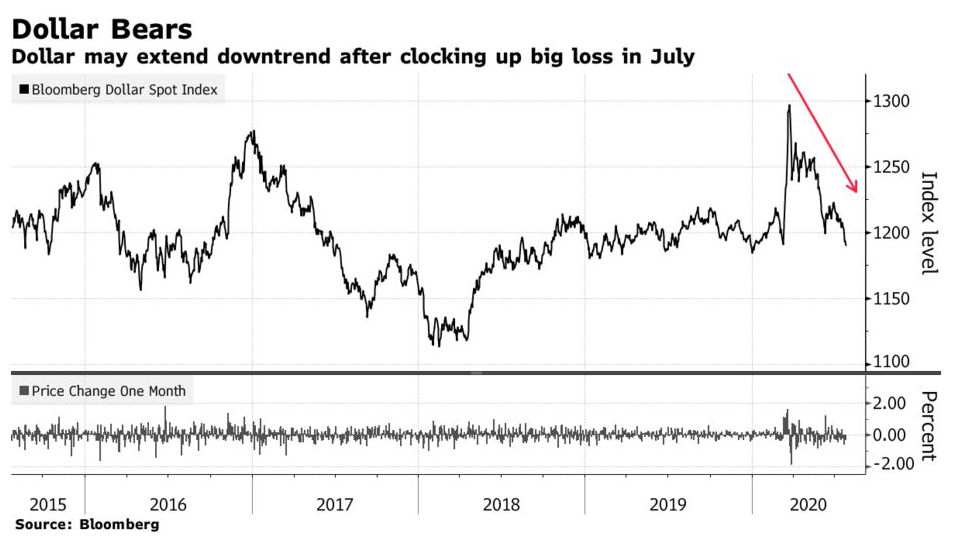

After trading over 29,000 the Dow saw large losses on Thursday after a week of gains. After the large run-up the last few months the losses could be from profit taking or the start of a market correction but there is no way to tell after one day.

Vaccine News

The US Center for Disease Control announced that states should prepare for a potential vaccine on November 1st. This would be great news heading into the end of 2020 and also right before the election.